Is there anyone, anywhere, ever, who hasn’t kept stumm about something not precisely true when put under pressure? Mostly it doesn’t matter but in the earnest chamber musical Dear Evan Hansen the ramifications are far-reaching.

Poor Evan Hansen. A misunderstanding that could have been dispelled in seconds takes on a life of its own, multiplying like a rogue cell under the light of a zillion social media likes and views and retweets.

The moment of lift-off is when awkward, lonely Evan Hansen (Beau Woodbridge) is mistakenly believed to be a friend – the only friend – of a druggy schoolmate who killed himself. Immediately he has cachet in the eyes of those who love to attach themselves to tragedy (“second-hand sorrow” as one character puts it).

Before Connor’s death Evan is effectively invisible. He is, he sings touchingly, waving through a window but no one sees. One of his classmates, amusingly officious Alana Beck (Carmel Rodrigues), definitely sees him now and kickstarts a campaign to acknowledge teen angst. It goes viral, Evan becomes a star and is embraced by Connor’s grieving parents.

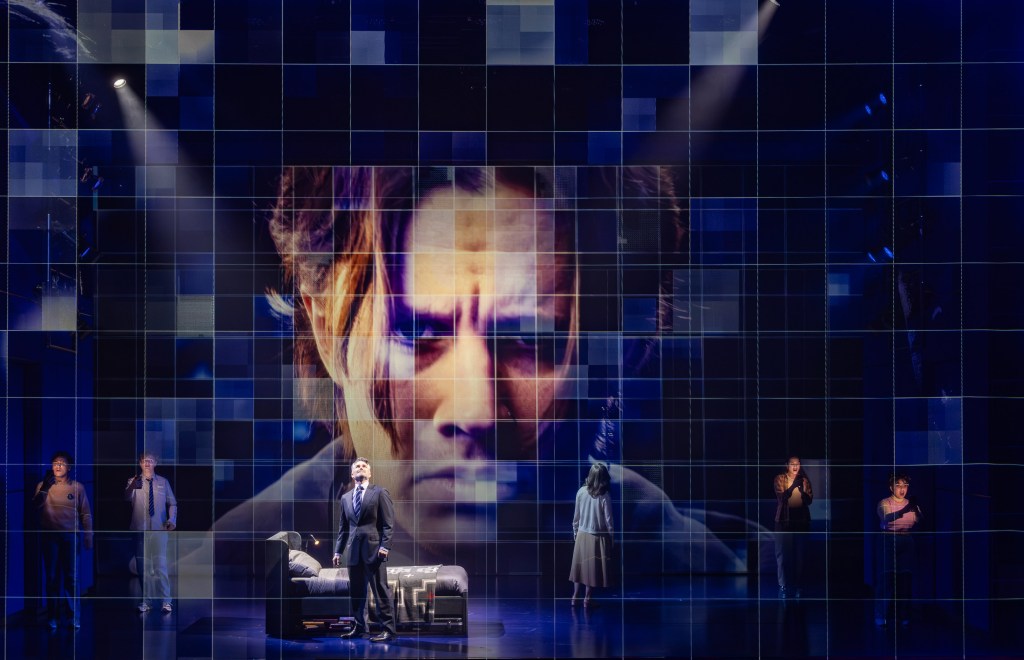

These are weighty matters and it’s up to Woodbridge, rarely offstage, to carry the load almost singlehandedly in this new production directed by Dean Bryant and given a clinical, high-tech design by Jeremy Allen. There’s a lot of social-media colour and movement, which is zippy and attractive, and furniture that slides in and out to indicate changes of location, none of it terribly inviting. Connor’s parents appear to inhabit a house as anonymous as a hospital waiting room. You get no sense at all of their lives, although one assumes that’s not the effect Bryant was reaching for.

Weighty matters as I say, although Dear Evan Hansen, written by the high-flying team of Benj Pasek & Justin Paul (music and lyrics) and Steven Levenson (book), treads more lightly than this precis suggests.

If Evan is hungry to be liked, so is the show. Alas in working hard not to be too offensive it does offend. Exhibit A is the dead Connor (charismatic Harry Targett), brought back as a ghostly adviser to Evan and now quite a spunk where previously he was briefly seen as an aggressive, slouchy lout. One song, Requiem, seeks to give various views of him but we never get a firm idea of why Connor was the way he was and why he killed himself.

Connor’s suicide is a clunky device used to set Evan on his path to acceptance. Its treatment sidelines thoughts of actual self-harm and clears the way for a brisk, often funny look at the commodification of tragedy. While that commodification is now seen everywhere and is a useful topic to air, it’s far from being the same thing as teen suicide. Here Connor is reduced to merch that needs to move quickly because his story will be displaced soon enough in the fast-paced world of teenagers. The kid’s death is nothing more than a hanger for other ideas.

Connor’s reappearance is really rather troubling. It suggests that someone can kill themselves and then somehow be around to see how people react to the loss. To still be a participant. Adults know about the finality of death; young people perhaps not so much.

Because we need to like Evan as much as he needs approbation, the deceiving of Connor’s distressed parents (Martin Crewes and Natalie O’Donnell) is at first given comic treatment as Evan and family friend Jared Kleinman (lively Jacob Rozario) concoct an email trail to prove Evan knew Connor well.

It’s another example of the wavering tone of Levenson’s book, although much can be forgiven a writer who slips in some stinging zingers, the most audacious of which is a reference to Connor’s look. “Very school-shooter chic” apparently. US audiences reportedly gasped at that line and why would they not? Here the opening-night audience gave a hearty laugh.

The show could perhaps be seen as a critique of social media although it’s not a particularly trenchant one. David Bergman’s video design is given prominence but it doesn’t seem a cause of Evan’s sadness. It merely amplifies the problem of a teenager profoundly disconnected from a world where the means of connection are ubiquitous.

Woodbridge’s Evan has a sweet, bright, eager, anxious face and a tendency to spill his words everywhere in a jumble. He’s a bit clumsy and has a painfully thin protective layer, particularly when with the girl he has a crush on, Connor’s sister Zoe (Georgia Laga’aia, smart and poised).

It’s an endearing performance and an optimistic one. In many ways he’s a fellow traveller of Muriel Heslop, another committed fantasist who just wants to fit in. Like Muriel, Evan will get better although his courage is not as well-developed as Muriel’s. He emerges from the mess relatively unscathed only through the understanding of Connor’s sketchily drawn parents, a kindness reported rather than seen.

Pasek & Paul’s pop-rock score is full of attractive songs, the best of which are for Evan (bar one) and sung gorgeously by Woodbridge despite being pitched treacherously high.

The score’s indisputable highlight, though, is given to Evan’s overstretched mother Heidi. The heartbreaking So Big/So Small comes almost at the end of Dear Evan Hansen and is a masterpiece of concentrated story-telling, superbly interpreted by Verity Hunt-Ballard.

Here is the quiet reflection, stillness, communication and human warmth Evan so desperately needs. The show could do with more of those qualities too.

Ends in Sydney December 1. Melbourne from December 14, Canberra from February 27, Adelaide from April 3.

This is an extended version of a review that appeared in The Australian on October 21.