Australasian Dance Collective is a small company that thinks big. Very big indeed when it comes to Lucie in the Sky, a piece for six dancers and five drones. The title has nothing to do with the Beatles’ Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds although that song’s “girl with kaleidoscope eyes” wouldn’t be out of place in the dance. Lucie is, in fact, a “versatile and nimble drone” (robotsguide.com) made by Swiss company Verity Studios and coded by them. That is, the drones were choreographed by them for ADC, in association with ADC’s artistic director Amy Hollingsworth.

Verity more usually provides large-scale spectacles for pop titans; here it’s working on an intimate scale, although one with great significance. Lucie in the Sky asks us to consider our relationship with inanimate objects that seem to have qualities we would describe as human. What do they make us feel? How and why do we connect emotionally with something made from pixels or, in the case of the Verity drones, 50g of plastic and pieces of code?

Hollingsworth started thinking about this about six years ago (before starting at ADC) and could not have been more on the money. The rise and rise of artificial intelligence applications makes the subject urgent. Kids have always played intently and creatively with toys and we have always ascribed human qualities to animate things but it’s a game-changer when these things appear to exist independently of our imaginations.

What could that look like in a dance work?

Lucie in the Sky puts all its participants, drones and dancers, on equal footing by giving each a name relating to Jungian archetypes. Or possibly the drones had a slight advantage in that each had a signature colour easily seen in Alexander Berlage’s necessarily crepuscular lighting. All the dancers, however, were in white, albeit most elegantly in Harriet Oxley’s individual designs. They weren’t so easy to distinguish at first glance.

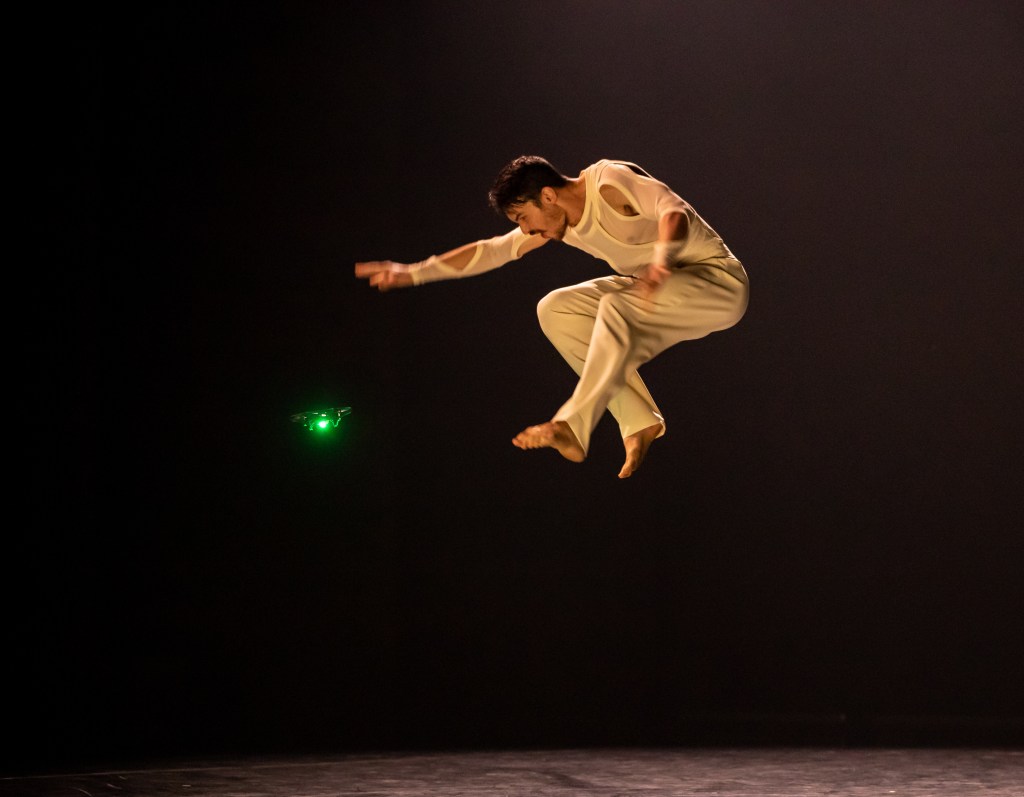

Green drone Skip played The Jester (it likes kissing strangers as well as well as flying loops, its program biography revealed) and had a thing with The Magician, danced by Harrison Elliott. These two had a lively, competitive relationship. The Caregiver (Chimene Steele-Prior) shared the stage with Lucie, the purple-hued Friend described as being shy, empathetic and loving. Those two pairings showed most clearly how a piece of plastic might be anthropomorphised.

Skip flitted about the stage looking jaunty and playful as it more or less buzzed Elliott. Elliott, meanwhile, dazzled with big tumbles, jumps and turns in the air – not easy when it was the dancer’s job to work within the parameters set by the drone’s programming. At one point Elliott appeared to have Skip land on a finger and then to flick it away. And believe me I’m finding it hard not to refer to Skip as he.

Steele-Prior and Lucie had a much quieter interaction that evoked calm and tenderness. A gentle light hovered in the near-darkness as a woman sat. Nothing could be more simple or more beautiful and it spoke volumes.

Without the performers the drones would be meaningless of course, and not all the interactions had the same degree of clarity as Skip/Elliott and Lucie/Steele-Prior. Sometimes, too, one wished for a scene to unfold at greater length (a terrific one for the whole group felt rushed) but there was a simple reason for the brevity: the drones could fly for only two minutes and 20 seconds before running out of power. Early days.

There was, nevertheless, a great deal of glorious dancing to Wil Hughes’s engrossing new score. It was electronic of course, as music for contemporary dance tends to be, and engaged powerfully with the work. Jack Lister (The Seeker) had an introspective solo that bore traces of tai chi. Lister and Taiga Kita-Leong (The Warrior) danced side by side in liquid, sinuous unison. Lilly King (The Artist) and Chase Clegg-Robinson (The Innocent) were both luminous and completed the multi-talented human cast that co-choreographed Lucie with Hollingsworth. M (The Leader), Rue (The Sage) and Red (The Rebel) were on duty for the drones.

On seeing Lucie in the Sky I was reminded of Kazuo Ishiguro’s 2021 novel Klara and the Sun, in which young people may be bought an Artificial Friend, humanoids who are capable of learning how to feel. Lucie is a more benign, hopeful work but it’s in the same neck of the woods. As Hollingsworth said at a fascinating forum following the Canberra opening of Lucie, “we shape systems and they shape us”. It would be a good idea to understand what we’re doing and why.