The contemporary triple bill Prism starts its Sydney season on November 7, after which, just for something completely different, The Australian Ballet will dive back into David McAllister’s blingy, ultra-traditional The Sleeping Beauty. It started its national run in Adelaide in July and had a Brisbane season in August.

It goes without saying the company is versatile. That’s a given in today’s ballet but there’s less than a week between Prism’s end (November 15) and Beauty’s start (November 21). Yes, dancers rehearse lots of varied repertoire all through the year and need to be nimble but these are full-out performances. Hats off to all.

There’s a lot of bang for your buck in both programs but Prism offers three ways of seeing ballet. William Forsythe is the revolutionary classicist, Jerome Robbins the boundary-blurring man of theatre and dance and Stephanie Lake the contemporary dancemaker, now part of the ballet fold, who shows just how far the boundaries can be stretched (it’s a long way).

It’s quite a workout and that’s just for the audience.

Forsythe was to have fashioned a new version of his Blake Works series for TAB (it would have been Blake Works VI) but illness prevented that. Instead, TAB presented Blake Works V (The Barre Project), made in 2023 for The Ballet Company of Teatro alla Scala. Forsythe, now 75 and one of the greatest living masters of dance, was happily able to come to Melbourne to polish the work and took a bow on opening night. That’s where I saw it alongside Robbins’s Glass Pieces and Lake’s Seven Days.

Each version of Blake Works (The Barre Project) differs in some details but not in essence. The ballet was created during the pandemic as a filmed work and later transferred to the stage, with later iterations made for companies including Boston Ballet and Dance Theatre of Harlem. It honours dancers around the world who kept up their daily practice however they could when prevented from appearing on stage and is now a living, evolving work that takes companies around the world into its embrace.

Forsythe pays homage to tradition but makes the familiar strange and new. It’s exhilarating. Also strange but compelling is the score, songs by British singer-songwriter James Blake that shimmer and echo. As a transparent, floating cloud of sound envelops the listener, movement is thrown off kilter, twisted, turned and accelerated and yet never loses its essential, radiant ballet-ness, even when a touch of cha cha swivels into view. This is ultra-high definition dance, presented with razor-sharp precision.

Among the many joys of Blake Works V is the brief homage paid to Danish master August Bournonville, another choreographer who knew what speed could do to a step. Absolutely central is the graceful tribute to the barre, the place where ballet always returns.

Forsythe closes Prism. It opens with Robbins, who has many claims to fame including bringing the now-ubiquitous Philip Glass to the ballet stage with Glass Pieces in 1984 (Glass was already well known in contemporary dance circles).

Glass Pieces is dazzling and mysterious all at once. The structure, rhythm, pulse, pattern and subtly changing repetitions of Glass’s music underpin absolutely gorgeous, utterly individual dance. The first section bubbles and swirls, the second delicately layers a long-breathing melody played by solo clarinet over a firm beat, the third gets the drums going.

In the opening, a large crowd’s walking, weaving and dodging morphs into unity with three pairs of sleek strangers who appear in their midst. Robbins called the duos visitors from outer space but equally they could be rich folk from the Upper East Side, given the busy Manhattan vibe of the piece (even if Robbins didn’t accept the idea of Glass Pieces as a portrait of city life).

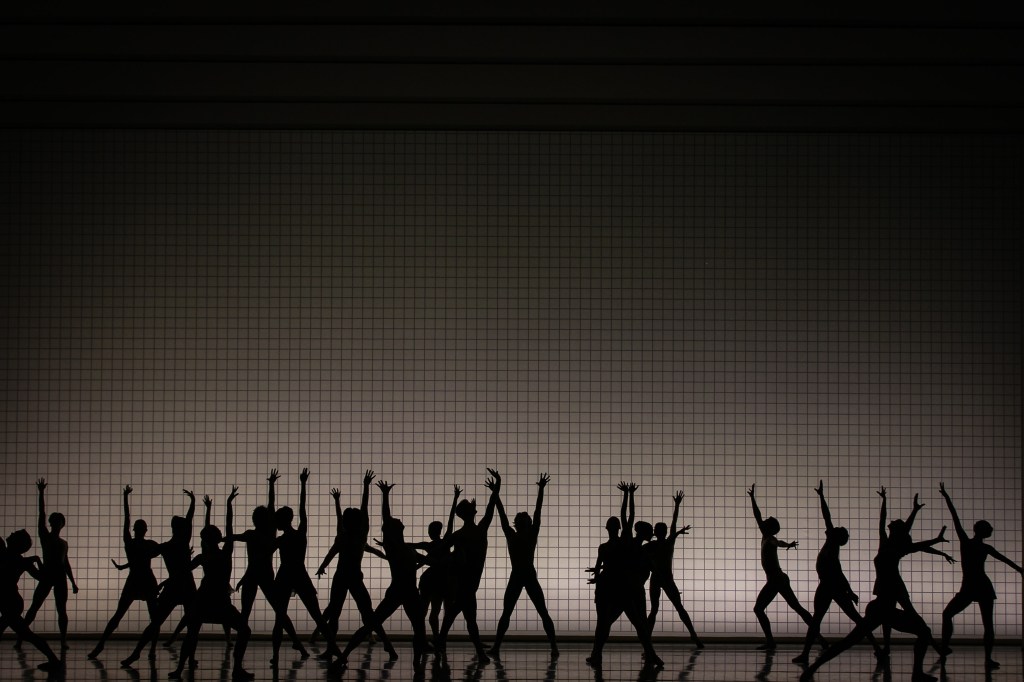

The opening is terrific but the central section is miraculous. It sets a soaring pas de deux against a line of women in silhouette, working their way across the back of the stage to the rhythmic undertow of Glass’s music. The opposition of aural and visual lines is entrancing.

Finally, 24 men and women raise an already high energy level, first in complex formal arrangements and then in high-spirited mingling to primal drums and blasts of brass. This third section sometimes recalls Robbins’s never-bettered choreography for West Side Story(1957) and perhaps looks a little old-fashioned in places. Or maybe enjoyably retro is a better description. Yes, let’s call it that.

Glass Pieces offers a smorgasbord of visual and aural stimuli. Somehow it all comes together in a feast for eye, ear and spirit.

It was wonderful to see Robbins danced by TAB after a long, long absence. The last time the company programmed his work was for a celebration in 2008 marking the 10thanniversary of the choreographer’s death. Perhaps TAB artistic director David Hallberg should now think about getting Robbins’s divine Dances at a Gathering for the company.

In between Forsythe and Robbins comes Lake’s brand-new Seven Days, danced to Peter Brikmanis’s increasingly freewheeling adaptations of Bach’s Goldberg Variations. The work starts quietly – is this Sunday? – and moves through a series of differently charged encounters between three women and four men.

The ferocious need for one another is touching. The group fights, huddles, separates, gathers and plays. Moods range from the evocative clarity of the introduction to madcap action at the end.

This tight little septet races through time and space with great passion and sometimes fuzzy focus. As in life, some days are better than others.

Lake’s initial and closing arguments, however, are strong. They anchor Lake’s constant theme, offered here in a series of variations, that nothing is more necessary than connection.

You could watch each of Prism’s three works again and again and again and still not exhaust their possibilities. Those interested in watching certain dancers closely could consider searching the Sydney cast list for principal artist Robyn Hendricks, senior artist Davi Ramos, soloists Isobelle Dashwood and Maxim Zenin and coryphées Samara Merrick, Lilla Harvey Benjamin Garrett and Elijah Trevitt. Many others are eye-catching but these shone in Melbourne.

Sydney Opera House, November 7-15.

This is a version of a review that first appeared in The Australian.